The first large-scale synthesis of the carbon budget in the shallow seas of the North West European shelf estimates that around 40% of the carbon entering the seas comes from the atmosphere and the rest comes from the land.

This finding is significant because it suggests that the NW European shelf seas absorb a volume of carbon comparable to UK domestic combustion emissions each year, and further demonstrates how human activities on land can have wide-reaching consequences for the health of coastal and shelf sea ecosystems.

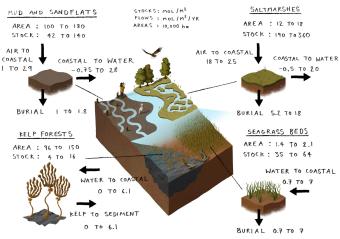

The study, led by the University of East Anglia, also found that most carbon processing occurs in the water column, whereas most carbon storage occurs in seafloor sediments. Regional management of the seafloor could therefore help manage and protect this important carbon store. Trawling was highlighted as being unique in that it is the only means of causing wide-spread disturbance to carbon stored in seafloor sediment that people have complete control over, although the overall impact of that disturbance is still being determined. However, it is the effect of global issues such as ocean acidification and warming where the most uncertainty lies.

Stacey Felgate, from the National Oceanography Centre (NOC), who was one of the authors of this research, said “This is another example of the important role the ocean plays in storing carbon which might otherwise be in the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.”

“It’s also important to understand the movement of carbon through the coastal ocean because it has a huge influence on marine productivity and food security. We also receive a wide range of benefits, beyond carbon storage, from coastal ecosystems like seagrass and salt marshes. These are integral parts of the land-ocean carbon cycle, and highly sensitive to change. Water purification, fisheries nursery grounds, coastline stabilisation, protection from storm surges, and increased biodiversity - all of these things are affected by the shelf seas carbon budget.”

“The findings outlined in this research will provide a reference point for policy makers who are looking for ways to manage carbon budgets, particularly as we head towards net zero carbon emissions by 2050, as well as a baseline for future studies.”

Published in the journal Frontiers of Marine Science this week, this study is the result of the highly collaborative, multi-institute Shelf Seas Biogeochemistry project funded by NERC.