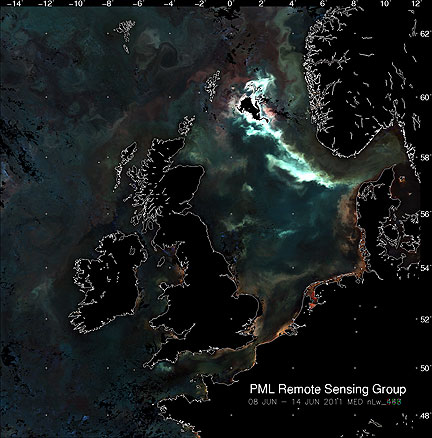

Ever since the first week of the cruise, we have been intrigued by satellite images showing a large and intense coccolithophore bloom in the northern North Sea.

Coccolithophores (see electron microscope image below and to the right) are microscopic phytoplankton, so small as to be completely invisible to the naked eye, no matter how sharp your vision is. They build tiny calcium carbonate shields (‘coccoliths’) and it is the light-scattering properties of billions upon billions of these coccoliths in the water that give the water its bright appearance from above. Imagine grinding up diamonds into tiny fragments and stirring those around in some water, with the light ricocheting and reflecting off the myriad fragments. This gives some idea of what’s happening in coccolithophore-rich waters and why their appearance is rather unusual.

We kept looking enviously at the satellite images that we receive on the ship, sent to us daily from NEODAAS, a specialist group in Plymouth. However, we started the cruise on the western (wrong) side of the UK, and knew it would be weeks before we would arrive on the eastern side, and that the blooms typically only last a few weeks. Therefore we didn’t expect it to still be there by now.

Thanks to heavy cloud cover during most of the last few weeks, we weren’t always able to see whether or not the bloom was still there, but then just a couple of days ago we received an image. The bloom was still there!

As discussed in an earlier blog, the possible impact of ocean acidification on coccolithophores is of considerable concern and debate, and is being actively researched. This bloom offers us an opportunity to find out more. We will make the most of the great array of expertise present on the ship to probe several aspects of the bloom here, including what is causing it, whether such blooms are still likely to occur in the future when seawater is more acidic (we plan to use bloom water for the next bioassay), and how the coccolithophores and the carbon chemistry of seawater affect each other.

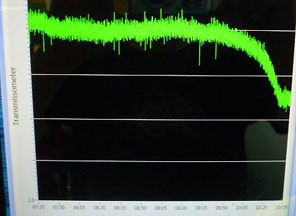

Once we realised that the bloom was still going to be there, we plotted a track directly across it. At first, as we steamed into where we thought the bloom should be, we saw nothing, and wondered if the satellite image was somehow misleading. Then one of us, Alex from yesterday’s blog, noticed that one instrument on the ship was starting to show an anomalous reading. The signal from the beam transmissometer (which measures how much of an emitted beam of light successfully crosses a fixed distance of seawater) was gradually declining, due to the coccoliths scattering some of the light. We were entering the bloom! Then, over the next hour or two, the colour of the water became increasingly bizarre when viewed from the deck of the ship, just like on other occasions when these blooms have been encountered at sea. It began to look, from the water colour at least, as if we were in tropical waters near a coral beach, rather than being in the normally greyish North Sea. The bloom waters are more aquamarine in colour, almost as if some milk has been stirred into the sea.

We have been busy through the rest of the day completing our transect and collecting lots of data across the bloom. We can already tell from the areas that we have surveyed so far that there are large numbers of single coccoliths but only a few living coccolithophore cells, almost as if we have come across a battlefield strewn with armour and corpses, but with the fighting all over. In this sense what has been called a bloom in this blog is actually misnamed because the coccolithophores have declined and are no longer rapidly proliferating. This may limit our ability to understand how the bloom formed, but we may nevertheless be able to make significant advances. Already the data that we have been collecting is leading us to reject some hypotheses we had entertained beforehand and to formulate some new ones.

Occurring intermittently and infrequently out at sea, not many get to encounter these blooms. It feels like a privilege to be able to see this curious natural phenomenon first-hand. We will see more of it over the next few days.

To find out more about these blooms, see www.noc.soton.ac.uk/soes/staff/tt/eh.